A tracking tool featured on many hospital’s websites has been collecting sensitive health information from patients and is sending it to Facebook. This information includes details about a patient’s medical conditions, prescriptions and doctor’s appointments.

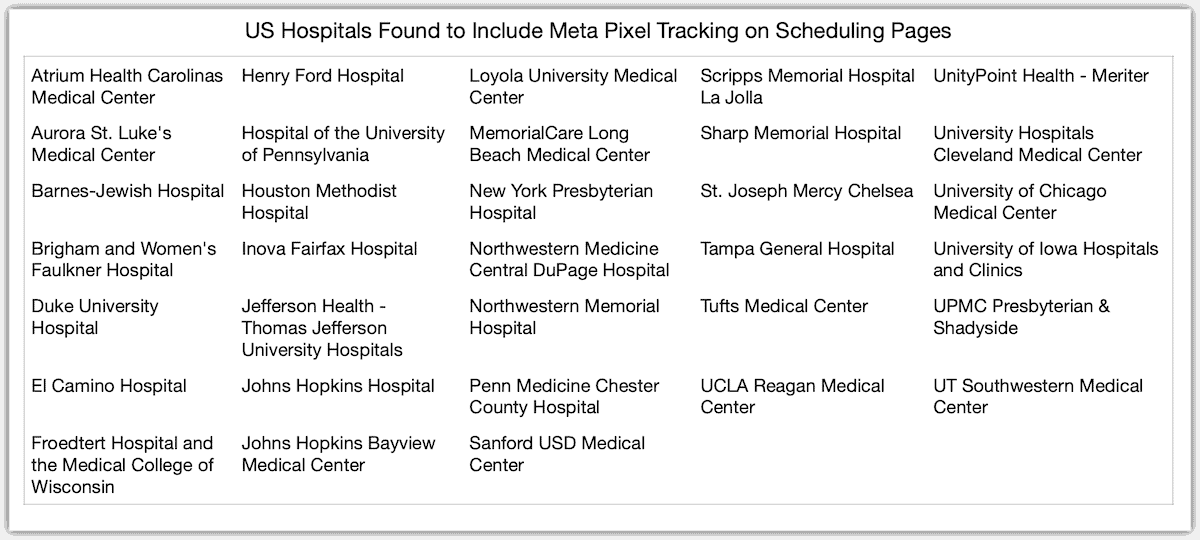

The report arrives from The Markup, who ran a test including websites from Newsweek’s top 100 hospitals in America. According to them, 33 of the sites had a tracker by the name of Meta Pixel. This tracker sends Facebook data whenever a person clicks a button to schedule a doctor’s appointment. This data connects to an IP address and creates a receipt of the appointment request for Facebook.

Meta Pixel Tracking Patient Information for Facebook

Meta Pixel helps track users while they navigate through a website. It logs which pages they visit, buttons they click and certain information that is entered into forms. One of the most prolific tracking tools on the internet, it is currently present in more than 30 percent of the most popular sites on the web.

In exchange for installing Meta Pixel, the social media giant provides website owners analytics concerning ads placed on Facebook and Instagram, as well as tools to help target people who visit their website.

For example, take the University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center’s website. If users click the “Schedule Online” button of the doctor’s page, it will prompt Meta Pixel to send Facebook the text of the button, the doctor’s name and the search term the website used to find her: in this case, “pregnancy termination”.

It was found that Pixel was installed inside password protected patient portals of seven health systems.

Additionally, The Markup also gathered data through real patient volunteers. In a collaboration with Mozilla Rally and The Markup, the crowd-sourced undertaking involved individuals installing Mozilla’s Rally browser add-in to send data to The Markup concerning Meta Pixel as it appears on a site user’s visit. The data shows that the information sent to hospitals includes the names of patients’ medications, descriptions of allergic reactions and details about upcoming doctor’s appointments.

Looking at HIPAA

According to several invested in the health community, including regulators, health data security experts and privacy advocates all state that the hospitals in question may violate the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

HIPAA prohibits covered entities, such as hospitals, from sharing personally identifiable health information with third parties. This excludes when individuals expressly content in advance, or certain contracts. Neither the hospitals contacted nor Meta said they had such contracts. There was little evidence to suggest that the hospitals or Facebook were obtaining express consent. HIPPA also lists IP address as one of 18 identifiers when linked to information regarding a person’s health conditions, care or payment, that qualifies as protected health information.

Furthermore, if a patient is logged into Facebook when they visit a website with Meta Pixel, some browsers are capable of attaching third-party cookies that allow Meta to link pixel data with specific Facebook accounts. This likely makes it easier for Facebook to obtain patient information.

As of June 15, seven hospitals removed pixels from their appointment booking pages. Additionally, at least five of the seven health systems that installed Meta Pixels in their patient portals removed those pixels.

Of the 33 hospitals discovered to be sending patient appointment details to Facebook they reported a collective of more than 26 million patient admissions and outpatient visits in 2020. This is according to the most recent data available from the America Hospital Association. It is worth noting that the investigation saw a limit of around 100 hospitals.

Response from Meta on Patient Information

It is not clear exactly how Facebook uses the patient information it obtains. The company did not respond to questions from The Markup. However, spokesperson Dale Hogan sent an email briefly paraphrasing the company’s sensitive health data policy.

Hogan writes,

If Meta’s signals filtering systems detect that a business is sending potentially sensitive health data from their app or website through their use of Meta Business Tools, which in some cases can happen in error, that potentially sensitive data will be removed before it can be stored in our ads systems,

Hogan is likely referring to a sensitive health information filtering system that Facebook launched in July 2020. The system was a response to a Wall Street Journal article as well a New York Department of Financial Services investigation. In the departments final February 2021 report, Meta had stated that the system was “not yet operating with complete accuracy”.

In the past, Facebook employees have expressed how well the company generally protects sensitive data.

Meta states within its business tools terms of service that the pixel and other trackers do in fact collect personally identifiable information for a variety of purposes.

Testing the Data

Going further, The Markup used both dummy accounts created by reporters as well as data from the Mozilla Rally volunteers. They found that Meta Pixel made it rather easy to identify patients. For example, when someone from The Markup clicked the “Finish Booking” button on a Scripps Memorial Hospital doctor’s page, the pixel sent Facebook not only the name of the doctor, but their field of medicine. The pixel also sent the first name, last name, email address, phone number, zip code and city of residence that was entered into the booking form.

While the Meta Pixel did “hash” the person details, that is, obscuring them through cryptography before sending them to Facebook. However, this does not prevent the company from using the data. Surprisingly, Meta was able to use the hashed information to link pixel data to certain Facebook profiles.

Scripps Memorial did not respond to questioning from The Markup. However, it did remove Metal Pixel from its appointment booking process.

In general, most of the hospitals contacted for the story did not respond to questioning. They also did not explain the reasoning for installing Meta Pixel. However, some did defend their decision to use the tracker. A spokesperson for Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago insists that the code was “vetted”. However, they were unable to explain the vetting process.

The Privacy of Patient Health Information

Additionally, Houston Methodist Hospital in Texas provided details to questions. According to the hospital, they began using Meta Pixel in 2017. A spokesperson for the hospital stated they were “confident” in Facebook’s safegaurds in not sharing information.

The Markup tested the Houston Methodist website. Clicking “Schedule Appointment” on the doctor’s page prompted Meta Pixel to send Facebook the text of the button, the name of the doctor and the search term used to find the doctor. In this instance, this term was “Home abortion”.

Houston Medical stated that this information does not fall under the category of protected health information. They state this is because a patient may not follow through and confirm the appointment. They may also be booking the appoint for someone other than themselves.

The hospital removed Meta Pixel from its website days after responding to questioning from reporters. It is worth nothing that the pixel saw installation three years before Facebook launched its filtering system.

‘HIPAA prohibits covered entities, such as hospitals, from sharing personally identifiable health information with third parties. This excludes when individuals expressly content [sic] in advance, or certain contracts. Neither the hospitals contacted nor Meta said they had such contracts. There was little evidence to suggest that the hospitals or Facebook were obtaining express consent. HIPPA also lists IP address as one of 18 identifiers when linked to information regarding a person’s health conditions, care or payment, that qualifies as protected health information.’

Nick:

Were FB (Meta) not so large an entity, and their business model and methods better descriptively circumscribed by extant corporate law, this paragraph alone would land them in court, being represented by an army of very nervous lawyers.

For anyone outside of social media corporations, and seemingly any entity that assigns itself access to whatever customer data their corporate leaders feel entitled (hotels, consumer store chains, restaurants, and similar high-security enterprises with a need-to-know our most vulnerable details), such a breach of non-consented patient confidentiality would be deemed a scandalous betrayal. Licenses would be suspended, trials would be held, and offenders fined and housed behind bars.

That all of these data end up at FB is no bug; it’s the point and the business model. Having discovered that other corporations, like Apple, are making it harder to hoover, FB have gone all in on deception, denial and concealment to steal our personal details. That’s what Meta meant by the system ‘not yet operating with complete accuracy’; their receipt of the data should not have been detectable.

Great pick-up on your part. Bad move on theirs.

Facebook and the person who runs it are irretrievable bastards.

The health systems that allowed it share guilt.

“It was found that Pixel was installed inside password protected patient portals of seven health systems.”

Is there a list of the health systems that are/were using this tracking bug?

Yes, it’s in the source article from The Markup. I’ll work on synthesizing it for inclusion here.

My doctors use MyChart.

I would bet some of the affected hospitals do, too. It’s not the individual patient charting system that’s been using the tracker, but the hospital’s web page. I added a chart of the 33 hospitals found to be guilty of using it.