Being conscious about digital security, considering the internet we have nowadays, isn’t easy. A couple of decades ago, anonymity was the norm; today, tracking and surveillance occur by default. A feasible way to stay somewhat safe is using browsers that respect your privacy, and macOS has some good options.

What Makes a Browser — on macOS or Not — Privacy-Oriented?

Every other day, someone creates a new way of tracking people online. Most companies say this allows them to offer “personalized experiences”—PR lingo for “spy on your browsing to display ads”. For some people, this may be an acceptable trade-off. However, not everybody wants digital salespeople repeatedly offering vacation packages because you once wanted to know the capital of Grenada.

There’s more to that than just inconvenience. As the name implies, online tracking involves creating a digital profile about you. This can be used for egregious stuff, like fine-tailored misinformation campaigns or even political persecution.

In smartphones, internet access is centered mostly in apps. Because of that, solutions to prevent tracking need to act system-wide. Both iOS and Android have gotten quite good at that in recent years.

In computers, however, people still use the web mostly from browsers. While system-wide tools aren’t harmful, browsers that hinder tracking technologies are practical for a few reasons. It’s way easier to develop (and update) a browser than a whole OS, for instance. Also, web standards that all pages must follow help mitigate some of the most basic issues.

Many browsers, by default, offer “customization” options during their initial setup, which are actually just disguised tracking permissions. Others apply settings that prevent tracking from the beginning. The latter group is what can be considered privacy-oriented browsers, and they’re available on macOS and many other platforms.

All Browsers Claim to Respect Privacy, Only a Few Actually Do

In recent years, many people have become more conscious about digital privacy, tracking, and cybersecurity in general. Companies noticed that — or, in many cases, were legally or judicially forced to stop ignoring. This is why you see so many “we respect your privacy” or similar statements from Big Tech these days.

That doesn’t mean, however, that they actually respect it. Meta’s Facebook and Instagram, for example, have their business model centered around advertising stuff to people most likely to buy them. Whatever promises Meta makes about respecting your privacy should be taken as seriously as a drummer promising to play quietly.

Other important examples are Google and Microsoft. Both hoard as much data as they’re allowed to (by you and legally), and frequently more than that. Also, both companies develop browsers, and both browsers have significant market shares.

Being Open Source Is Not Enough

The most common argument against this is that Chrome and Edge are based on Chromium, an open source browser. While true, this doesn’t mean it’s tracking-proof. As recently as 2024, Chromium-based browsers have been caught sending detailed data about their users’ computers to Google. Reports of similar issues have been around since at least 2010.

Other browsers not only claim to respect your privacy but also use this as a major sales point. That’s the case with Opera, Brave, Vivaldi, and Firefox.

Firefox, which used to be the last resort for online privacy advocates, came under fire recently. In late February, Mozilla, the nonprofit behind the browser, announced its Terms of Service (ToS), sparking a lot of controversy. The writing is vague and could allow the organization to use information you input into the browser for questionable purposes. At the same time, Mozilla removed the decades-long pledge not to sell user data from its website.

The other examples require some historical digging. Since this is not the main point of this article, I’ll keep this as brief as possible. Linked sources provide further details.

Some of the aspects aren’t directly related to user privacy but will be listed nonetheless. The idea is to provide information that can be relevant when deciding whether to choose a specific browser/platform.

Opera

The company itself was acquired by a Chinese investment fund in 2016. After that, it became a financial operator (pun intended) for predatory loans in African and Asian countries.

Around that time, the browser had launched a “VPN” service—which was actually just a regular, less safe HTTPS proxy. Opera’s representatives kept claiming it was a VPN, though. Other claims, like that it disguised the user’s IP address, for example, were also found out to be false.

Brave

Likely the browser that advertises itself the most as a privacy tool, Brave has lots of problems as well. For starters, it doesn’t block all trackers — on purpose. Its Rewards program, which requires a lot of personal info, merely replaces ads you’d see anyway with their owns.

Also, Brave has been caught adding affiliate code to URLs — simply put, the browser manipulates addresses of sites you visit. It also runs background processes, with system-level privileges, which remain active even if you uninstall Brave.

There’s more: early versions of its Tor feature leaked user data. As if things couldn’t get worse, the company also requested donations in name of people that didn’t consent to that. These people also didn’t receive any of the donated money. Or “money”: the donations were made in BAT, Brave’s own cryptocurrency. At least, the donors were eventually refunded. Finishing the privacy-related issues, the browser also installed a (paid) VPN service on users’ computers without consent.

On other topics, Brave’s founder, Brendan Eich, resigned ten days after being named CEO of Mozilla, back in 2014. The reason? He was about to be ousted for opposing same-sex marriage. Holding conservative beliefs isn’t a crime (though the morality of it is debatable), but forcing them on others is wrong. And that’s precisely what happened: he tried to make an alt-right Wikipedia knock-off Brave’s default search engine.

Vivaldi

Another Chromium-based browser, Vivaldi manages to be worse than the above alternatives in some ways. For starters, it uses lots of Goole stuff — parts that aren’t at all required to make a Chromium-based browser.

Vivaldi also “phones home” every 24 hours, sending details about your computer, your approximate location, and a unique identifier. This data is logged, and the company doesn’t disclose for how long it keeps the information stored. Among many other issues, Vivaldi also has WebRTC enabled by default, with IP broadcast turned on, a decade-old security oversight.

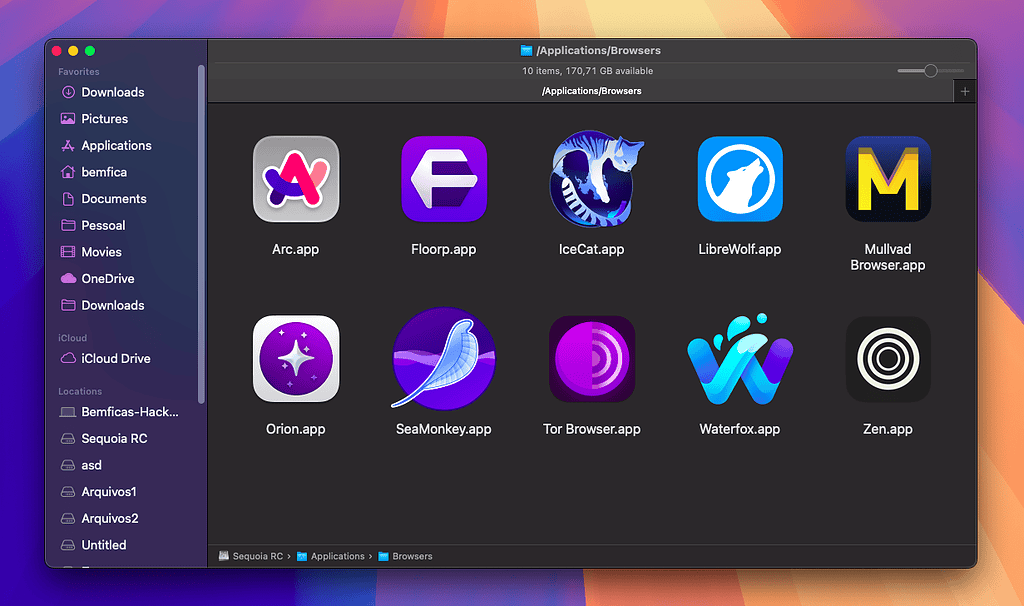

Best Privacy-Oriented Browsers for macOS

Most, but not all, of the recommendations below are based on Firefox. They all use that base similarly: fork Firefox’s code, strip it off of “bad stuff”, then add some personal touches. The “bad stuff” is, in general, telemetry collection, non-open source stuff, and user tracking components. Mozilla’s Firefox branding is also removed, since the browser’s license forbids distributing modified versions under the same name.

One thing most Firefox users may miss, if they want to get rid of everything Firefox-y, is using add-ons. You can install them in any Firefox variant, but they’re still served through Mozilla, which can be unwanted by some.

GNU, the software suite made by the Free Software Foundation, has Mozzarella, which serves a similar purpose. The repository houses free and open source extensions that can be used in any Firefox-based browser.

Migrating From one Firefox-Based Browser to Another: the Easiest Way

One last thing before we move to the list. Most of the Firefox-based won’t offer a native way to migrate your data from Firefox. Some of them support Firefox Sync, which unfortunately is very limited.

When trying to find a complete solution, I stumbled upon this workaround in GitHub. Despite being posted in a Zen-related discussion, it works wonders for any Firefox-based browser.

After copying everything, it will be as if it was the same browser. Your cache, cookies, login sessions, saved passwords, bookmarks, absolutely everything will be just as you left it before closing Firefox.

1. GNU IceCat

Starting with IceCat, which is possibly the most straightforward variant. Except for the different branding, IceCat has nothing added to its code after removing the “problematic” Firefox parts.

IceCat, like some other GNU software, isn’t available as an app you can just download and install. You have to compile it from source. There is, however, an unofficial repository which keeps binaries for different OSes, including macOS.

The drawback is that these binaries are usually somewhat old: the newest ones are based on Firefox ESR 115.22. The most recent macOS build is based on version 115.17. ESR stands for Extended Support Release, versions that are maintained for longer.

However, Firefox ESR 115 is recommended only for older versions of Windows (7-8.1) and macOS (10.12-10.14). Users on macOS Catalina (10.15) or newer are advised to use the newest ESR version, 128. There’s no indication of when GNU developers will start basing IceCat on this version.

2. Tor

Any deeper search for privacy-oriented browsers will mention Tor, which is available on macOS, Windows, and most Linux distros. Many misinformed stories about “the deep web” will mention Tor as well, ut these can be safely ignored.

Simply put, Tor uses several relays to disguise the origin and destination of your traffic. Basically, instead of accessing a website directly, your requests pass through various computers, with the response following the inverse path. While it’s (technically) true that you can only browse .onion pages using Tor, the browser can also cloak any traffic. Therefore, you can use Tor for day-to-day navigation, though its modifications for strengthened security may break some features.

3. Zen

When I decided to leave Firefox, the first alternative I tried was Zen. It looks great, works great, but simply isn’t for me. If you’re not against vertical tabs, it’s worth a try. You might need to un-learn and re-learn quite a few things about how you interact with browsers, though.

One significant limitation of Zen is that, for now, it doesn’t support DRM. Because of that, most streaming services won’t run on it. Simply use another browser for this purpose, but the developers say they’re working on this.

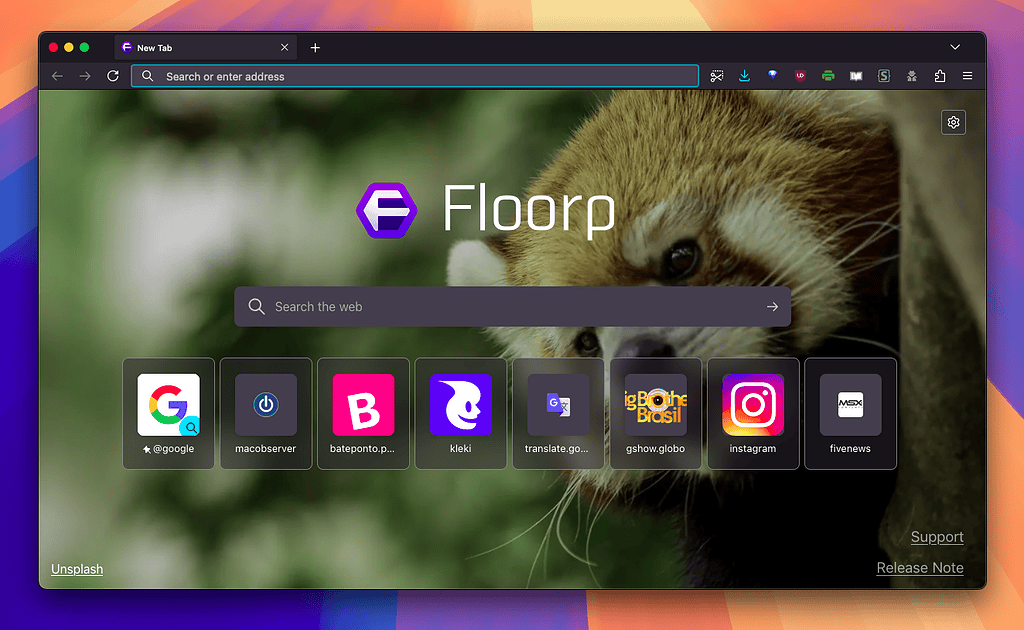

4. Floorp

Floorp is what I ended up settling on. It’s pretty much the same as Firefox, design-wise, though the next version is posed to receive significant UI changes. That also means there aren’t functional changes between Floorp and Firefox, so there’s no learning curve.

Floorp is made by Ablaze, a Japanese collective which defines itself as a “community of developers”. That’s pretty much how Mozilla was described, when it was founded, and I think this is a very good sign.

5. LibreWolf

Among cybersecurity enthusiasts, LibreWolf is one of the most popular Firefox alternatives. It’s almost the same as IceCat, in the aspect of being Firefox with all the questionable parts cut off.

LibreWolf, however, has additional privacy and security settings. This may make it difficult to use for some stuff, like online banking, though. Therefore, I recommend you keep a backup browser handy — Safari will likely do the trick. Also, DRM is disabled by default, so you may need a separate browser to play DRM-protected content.

6. Waterfox

Waterfox is very similar to LibreWolf in most aspects, though a bit less restrictive. It also has a significant focus in customization, if you like to change your browser’s looks. Lastly, Waterfox supports playing DRM-protected content out of the box.

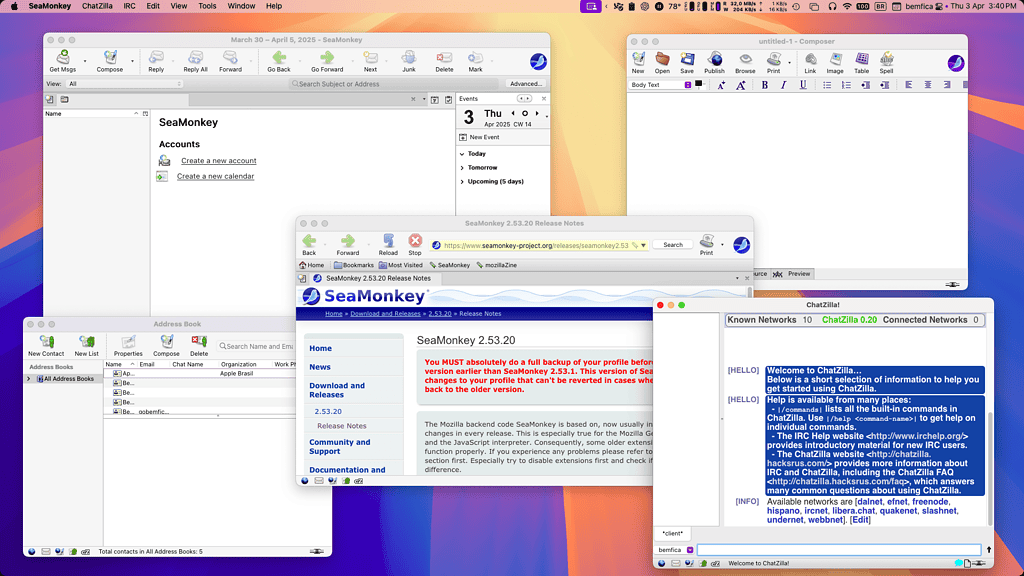

7. SeaMonkey

If you have been a Firefox user for a very long time, you might remember the Mozilla Application Suite. It was the open-source version of Netscape Communicator, from which Firefox (then Phoenix) would eventually be forked in 2002.

In 2004, Thunderbird was also separated from the suite, and Mozilla ceased development. The project was picked up by a group of volunteers, and this became SeaMonkey.

That means SeaMonkey is more than a browser. There’s also an e-mail client, an address book, and even an instant messenger for protocols like XMPP and IRC. SeaMonkey has its own addon repository, since there are more features extensions can work with than in regular browsers.

8. Mullvad

Swedish company Mullvad is better known for its VPN, which is a paid service. It also develops, however, the Mullvad Browser. It is designed to integrate seamlessly with the VPN, but can be used without it.

Unlike the VPN, the browser is free. It’s developed in partnership with the Tor Project, and, like Tor, has private navigation as the default browsing mode. The main difference between them is that Mullvad can connect to the internet without accessing the Tor network.

9. Orion

Originally, Kagi is a paid service that promises do de-shittify Google’s search. It also has a browser, Orion, which is focused in privacy.

It’s based on Apple’s WebKit and features vertical tabs with tree navigation. There’s also support for extensions made originally for either Chrome or Firefox, and synchronization between devices.

Orion is still in beta, but most features planned for the final release are already available. One thing to have in mind is that Orion isn’t open source, so it’s not auditable by the community.

10. Arc

Arc, by The Browser Company, also promises to put its users’ privacy first and foremost. Like Orion, it’s closed-source, so there’s really no way to guarantee that.

However, if you’re coming from Chrome or Edge, for example, there’s absolutely nothing to lose on that matter. In addition, Arc looks amazing, and has features like tree structure for tabs, workspaces, and split view.

Bonus: Ladybird, a New Browser Engine (That Won’t Be Available for a While)

Lastly, I can’t finish this article without mentioning Ladybird. Right now, Ladybird isn’t available for end-users — and won’t be for some time. That’s definitely a name you should keep your eye on, though.

Ladybird’s goal is to create a new browser engine, from the ground up, to compete with Blink, WebKit, and Gecko. Though external, open source libraries are required for the development, no code from existing engines will be used. That’s possibly the first time something of that magnitude is being tried in over 20 years.

To fund that, Ladybird’s creator, Andreas Kling, set up a nonprofit. He seems to be up to the task: previously, Kling had created a whole computer OS, SerenityOS, also from scratch. Among the project’s backers is Chris Wanstrath, one of the founders of GitHub.

The major downside is that Ladybird will take quite a while to be available. According to a post by the project’s Twitter X account, the goal is having an Alpha version ready by 2026. A Beta is expected for 2027, with general release coming only in 2028.

Settling on a browser can be a tiresome task by itself. If you consider additional requirements for that browser, like strong privacy protection and macOS compatibility, it becomes even harder.

While there are quite a few options available, each of them will require one or two compromises, at least. That said, things aren’t great but aren’t terrible either, and the situation could be way worse. Now, it’s up to you to decide which option to choose. Or maybe, I don’t know, try all of them for a while.